Stop Acting: How One English Literature Quote Can Fix Your Approach to Fitness and Training

What if the best way to understand the modern fitness journey isn't through science or economics, but through a classic idea from English literature: Shakespeare's metaphor that "All the world’s a stage"? If we treat this idea as a critical lens, we can start asking some tough questions about what we truly value when we train.

The Uncomfortable Questions of the Gym as Theatre

Shakespeare’s line, from the play As You Like It, suggests human life is a performance, and we are all just actors. If we accept the gym as a theatrical space, where we adopt roles, wear costumes, and follow scripts, a lot of questions immediately spring up:

The Costume: When you choose your specific, often expensive, workout gear, your 'costume', are you doing it for function (better performance) or for signalling (better status)? How much of your fitness budget is spent on being perceived as dedicated, rather than actually being dedicated?

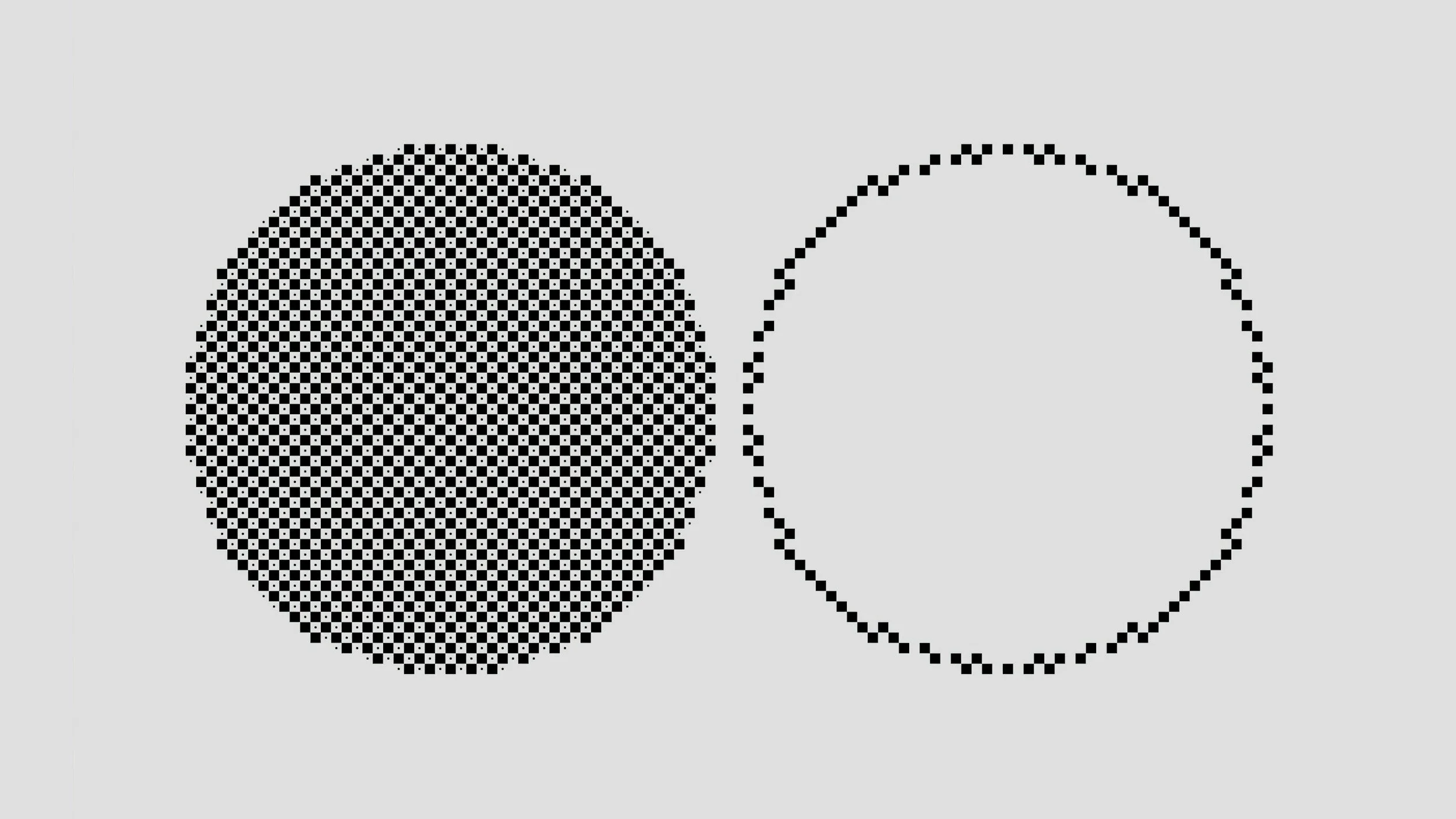

The Set: Why are most modern gyms dominated by mirrors and bright lighting? Are they designed to help you check your form, or are they specifically placed to encourage you to monitor yourself as an object of display? Does the physical layout encourage genuine focus, or performance for others?

The Audience: Who is your workout really for? If you stopped documenting your progress—taking photos, tracking apps, filming lifts—would you still put in the same effort? If the 'audience' (whether in the gym or online) disappeared tomorrow, what would be left of your motivation?

Unmasking the Performance Trap

When we forget that the gym might be a stage, we risk confusing the performance with the real thing. This confusion raises deeper questions about our priorities and the potential consequences:

The Effort vs. The Spectacle: Why do people often choose highly technical, challenging, or heavy exercises that look impressive (the spectacle) over simpler, more effective movements that serve their individual health goals (the effort)? Are we unconsciously scripting ourselves into roles that prioritise appearance over safety?

The Currency of Attention: In a world where attention is currency, are we prioritising external validation (likes, comments, glances) over internal rewards (better sleep, improved mobility, reduced stress)? If we only feel successful when others acknowledge our work, is that true fitness, or is it just acting?

The Risk of Burnout: If your only motivation is tied to the dramatic 'role' you play, the 'fit person', what happens when the show is over? Is the high rate of fitness burnout and dropping out a direct result of people mistaking an exhausting social performance for a sustainable, personal health journey?

The Question of True Significance

Why does resolving this confusion matter? Ultimately, if you gain the ability to spot the theatre in your routine, you can start asking the most important question of all:

Are you honestly expressing yourself? If you are the director of your own fitness 'play', are you directing a show that leads to genuine, long-term health and happiness, or one that’s exhausting, superficial, and designed only to impress a temporary audience?

By using Shakespeare’s stage metaphor to challenge the assumptions of gym culture, we force ourselves to look past the lighting and the gear to ask what the true purpose of our performance is.